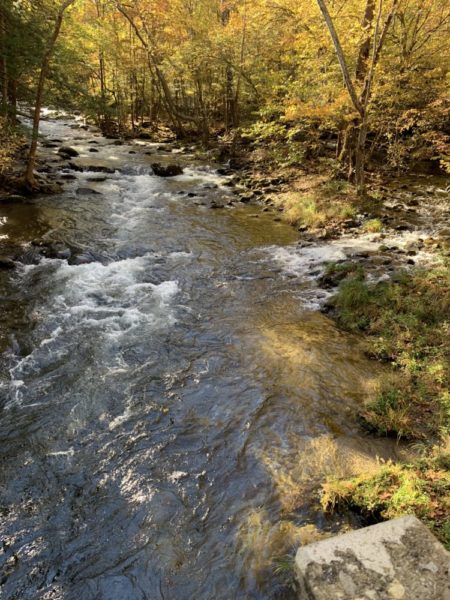

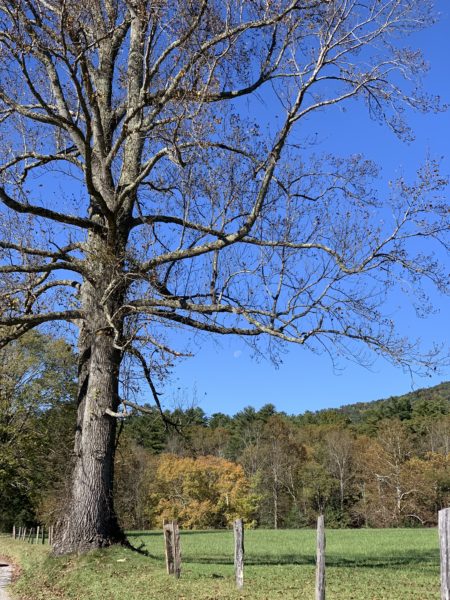

The sun was shining; the trees were glowing.

On our way to Asheville, North Carolina, we took a side trip in the Smokies and drove the Cades Cove Auto Loop. It was a lot of extra driving, but well worth the time. The trees were like a towering cathedral, the interior a sacred space.

Open spaces gave a view of the countryside. These clearings were first settled by Europeans in the 1830s. Deer and turkey were plentiful along the route, but none conveniently posed for a photograph.

Cades Cove Methodist Church, built by John D. McCampbell. The white frame structure has two front doors, a design that was common in the 1800’s in the Smokies.

Spots of color brightened the way along the 11 mile loop road. Though the traffic was not bumper to bumper, it still took several hours to follow the loop.