https://www.petwantsclt.com/petwants-charlotte-ingredients/

Cheap Tramadol Next Day Delivery “Travel isn’t always pretty. It isn’t always comfortable. Sometimes it hurts, it even breaks your heart. But that’s okay. The journey changes you; it should change you. It leaves marks on your memory, on your consciousness, on your heart, and on your body. You take something with you. Hopefully, you leave something good behind.” – Anthony Bourdain

For nearly a decade, I spent the winter months in Arizona. I drove from Wisconsin to Arizona after the Christmas holidays and returned to Madison in early May. The time in solitude, challenging in many ways, was also life-affirming and regenerative. I cherished those sunny days in the desert and yet I missed Wisconsin. When May arrived I was always ready to return to family and friends and to the Midwest’s more moderate clime.

On May 1st, 2014 I began the 2,000-mile solo drive from southern Arizona to Madison.

On the second day out, I left a motel in Sedona at sunrise, eager to be in Santa Fe by early evening. But when I turned the key in the ignition all the warning bells and whistles on the dashboard started flashing and beeping. Sedona would have been a great place to be stranded, but there was no available Subaru mechanic and so my car was towed to Flagstaff. After two days of delay, I was told there was a head gasket issue which would require a lengthy stay in the repair shop. The shop assistant set me up with a loaner car with unlimited miles and said, “Come back in a week.”

I had an unexpected week to explore northern Arizona, a region I had never really explored. Yay!

I headed north from Flagstaff, Arizona and took the scenic route. I was on my way to the North Rim of Grand Canyon National Park. I planned to meet a photographer I knew only from her online photo blog who worked as a Park Ranger during the North Rim’s short summer season.

On the second day of my unexpected adventure, I stopped at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument and asked the Park Rangers to recommend a hike. They suggested the Toadstool Trail, a mile and a half long trek through balanced rocks and hoodoos in Utah’s Escalante Wilderness.

“Be sure to hike past the first toadstool,” one ranger said. “The toadstool garden is quite the thing to see.”

While browsing the park literature, a line from a National Park Service brochure caught my eye:

https://www.petwantsclt.com/petwants-charlotte-ingredients/ “offers…extraordinary insight into what sustains, maintains, and explains our world.”

Sustains. Maintains. Explains. Yes, that was exactly why I explored the wilderness of the Southwest.

At the trailhead, I checked my hiking pack. My Sonoran Desert gear was appropriate for high desert country. I was on a marked trail so I didn’t need much. It was mid-afternoon and I knew I’d have good hiking light for several hours. The temperatures, hovering in the low 90s, would soon cool and make for a more comfortable experience.

I was twenty yards down the level trail when I reconsidered my choices and went back to my car for my hiking stick and extra water. I tried to relay my hiking plans to my friend, something I always do when I’m solo hiking, but I was in a “no service” area. Still, I was on a popular trail, so I didn’t consider this a problem. Off I went.

The trail followed a sandy wash for the first half mile, then wove around sculptured slick rock. Small daisy-like wildflowers bloomed in abundance. I took lots of photographs, lingering at scenic spots, but then, every place I looked was a scenic spot. Formations of striped red and white made for a stunning backdrop. The sky was azure blue and cloudless.

Two twenty-something hikers passed me on their return and I heard them marveling at the hoodoos and balanced rocks.

“The toadstools,” they thrilled to each other. “They really look like toadstools. It’s amazing.”

I reached the first toadstool, a thirty-foot beauty standing in solitude. A group of tourists from California was gathered at its base, taking photographs. They assured me that the toadstool garden was just beyond the white escarpment, exactly how the ranger had described it.

“How’s the trail?” I asked.

“There’s some scrambling through the rocks. But the garden’s so worth the climb.”

I was good to go, grateful I’d brought my hiking stick. The backcountry was rocky and uneven, and there was a modest climb in elevation.

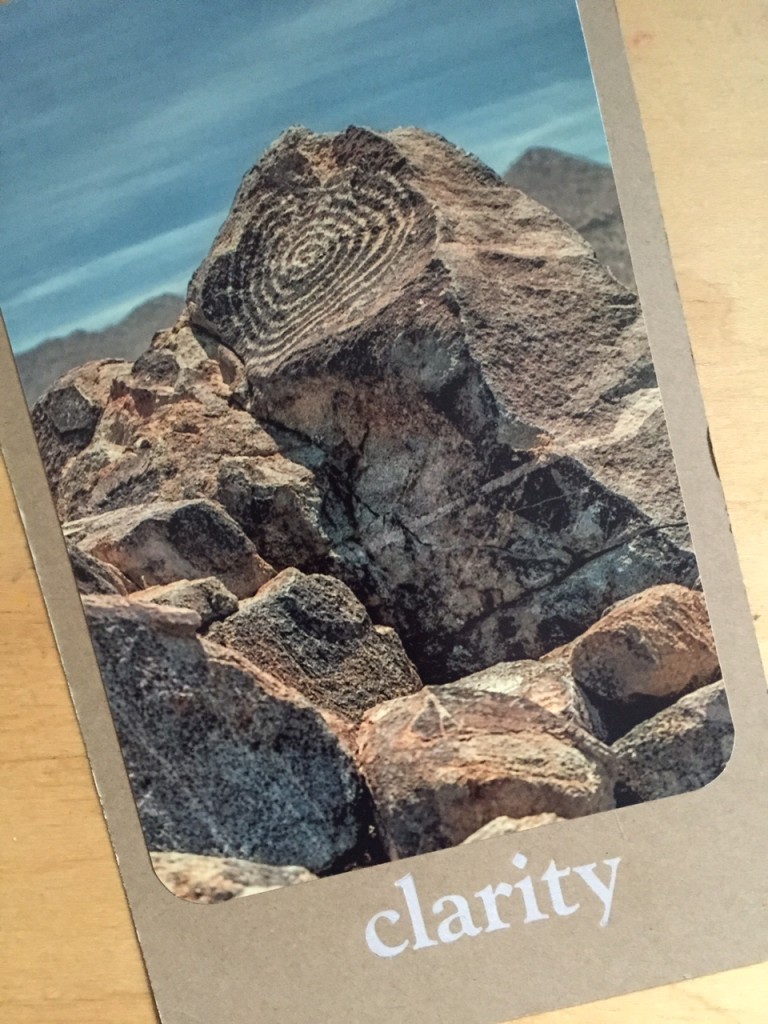

Cairns marked the dusty trail. I wound through narrow channels and crossed long benches of red rock. When I finally reached the garden, it was, indeed, well worth the effort. It was difficult to photograph because of the shadows, but the scenery to the west was strikingly wild, eery, otherworldly.

I’d been out on the trail a couple of hours, appreciating the solitude and sights, but I needed to get back on the road so I retraced my steps along the trail. But as I was scrambling through a narrow pock-marked passage in the chalky rock, I realized I’d crawled over these rock formations before. I was walking in a circle.

I retraced my steps to the last cairn, but no matter which trail I followed, I kept coming back to the same formations. I was walking in a wide circle, following a path half hidden in rocky crevices. The trail disappeared as I searched for a new route and I realized that I was alone and lost in a tangle of rock hoodoos.

I didn’t panic but instead tried to sort out the facts. I had plenty of time. It was evening, but the days were lengthening. It would be light for another hour. Again I carefully retraced my steps, but I the turn or switchback that would lead me to the main trail eluded me. I began feeling frightened and I remained calm.

Deep breaths. I checked my pack. I had enough water, a few trail bars and some dried fruit. I didn’t have a flashlight or any type of protective cover. I had a whistle and an extra bandana. I could make do.

I considered my options. Sleep under a ledge for some protection and warmth? Lean against the rocks and stay awake? It was only for one night. There would be hikers on the trail in the morning. I’d never spent the night unprepared and alone in the wilderness. Was this going to be the night?

I considered the merits of spending the night in high country, alone except for the vast desert rock and the night sky, with rock as my bed and starshine and moonlight as my lanterns. It would be challenging, but doable. It might even be enjoyable.

I’d settled into a rocky depression, and was watching for the first stars of the evening to appear, when I saw two hikers maneuvering along a rocky ledge, high on the opposite side of the crevice. I whistled three sharp blows. They looked towards the sound and saw me. We communicated using hand signals and shouts. They realized quickly that I was off trail and couldn’t find the path.

They had a height advantage. They scanned the rocky puzzle below them, considering the rocks, the paths. Then they pointed the way, guiding me through the deep shadowed crevices and around boulders. Finally, I scrambled up a rocky wall and I was once again on the trail.

We walked together towards the road. At the first solitary toadstool, they asked if I would take their photo – they were father and son, New Yorkers, on their annual visit to the Utah Wilderness and wanted a memento.

Once we were on the more-established trail, I slowed down, motioned them to go ahead. I needed some quiet time to think about this experience, the realization that I’d been lost and had not panicked, that I was capable of spending a night alone in the wilderness of the red rocks.

It was in getting lost, that I had indeed discovered innate strengths I had not known I possessed.

It was in the getting lost that I actually found myself.